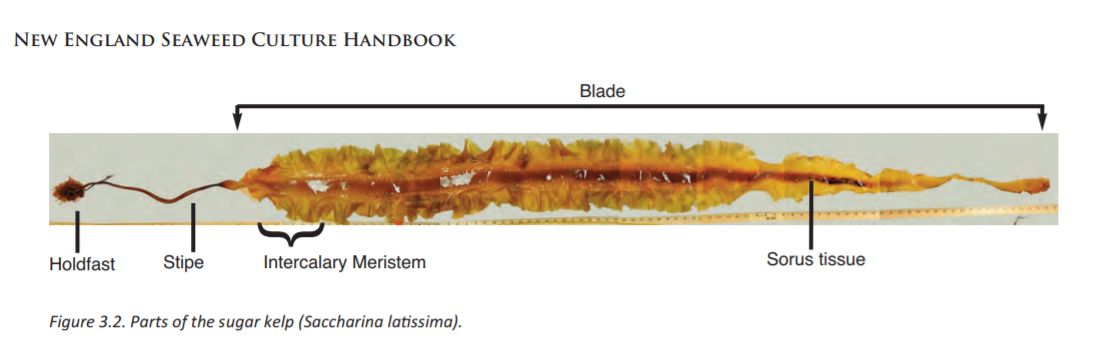

No mom, we didn't buy a part of the ocean. Actually, this is a question we got a lot. We did have to lease an area located in state waters which is designated as a site appropriate for aquaculture (think oysters, mussels and stuff like that). The farm is all underwater. Kelp is a sea vegetable, but a really important difference between sea vegetables and land vegetables is kelp doesn't use its roots to adsorb nutrients from soil like spinach or kale. Because of this, kelp's "roots" (they are really called the holdfast which is pretty straight forward) are just used to attach the kelp to something underwater where the kelp can grow and absorb nutrition from the sun and the passing water. In nature, kelp can grow from the bottom of the ocean up (sort of like grass), off the side of a rock, or in our case, from a line downwards (sort of like the branches of a weeping willow). The kelp seed comes from a hatchery and is handed over to us in a spool - more specifically a spool of kite string. The actual farm is all underwater (with a few buoys on the water surface to make sure things don't sink to ocean floor). It looks a little like this low-rent post-it drawing featured above.

The spooled kelpy-kite string is unrolled around a horizontal line about 5 feet below the surface of the water. Imagine a balloon on a long string tied to a rock - now imagine another one about 200 feet away. We tie the kelp seed line to each of those anchored balloons (buoys) and let it sit in the ocean - it can't sink and it wont float away because of the anchors (we hope!). It grows downward allowing us to harvest it easier. We can also check on it without diving in the ocean in the middle of winter.

Where are you getting the kelp seed?

UConn and the Connecticut Sea Grant have been looking at kelp and ways to germinate and cultivate the plants. They have partnered with Bren at Greenwave (the glorious NGO we are working with) to get the right type of seed to the farmers. Divers go out in the early fall and harvest seed from wild kelp forests that are growing locally. They collect sorus tissue which has the spores for future generations of kelp and bring it back to UConn. The seed comes to us in spools of "seed-line" and all we need to do is string it out in the ocean and pray it works.

Would Jay and I actually eat it?

OF COURSE we will...so will our cruddy kids and so will everyone who comes to our house. We will also drink it (stand by for more on that). It can be really good for you.

How do you get it once it grows?

Nothing we are doing here is high tech. The harvesting is fairly simple - you go to the kelp farm, use your hands or a winch from the boat to lift the heavy (hopefully) kelp line from the water and you cut the kelp off with scissors. You then place it in a bin and rush it back to the processing plant. Kelp needs to be processed right away to keep it usable. This is a race against the clock. Once it is at the plant, it is cleaned, blanched, and frozen in under 24 hours. Jay and I will be a part of this process.

What do you use kelp for? / Who is going to buy our kelp?

Greenwave has helped us navigate the process from seeding to selling. They have worked with for profit organizations such as Sea Greens to establish market demand for kelp and explore new avenues of application - for instance kelp can be used as fertilizer, as fuel, in cosmetics, and as food for humans and animals. Jay and I are the farmers who sell to value-added businesses like Sea Greens. They take the kelp and turn it into what the market wants. Jay and I, obviously, will retain some of the product to mess around with and to share with you good people. I hope to offer kelp to local restaurants directly as well as bring to CSAs or farmers markets. Why not, right?